On June 29, 2023, the Supreme Court overturned affirmative action in American college admissions. In a divided decision for two separate cases, the Court ruled in favor of Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), declaring that Harvard University and the University of North Carolina’s (UNC) use of affirmative action was unconstitutional.

Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her dissenting opinion :“Today, this court overrules decades of precedent and imposes a superficial rule of race blindness on the nation”.

Affirmative action was a policy in college admissions considering certain individuals’ races as a factor in a college application, if they are considered to be an underrepresented minority. With college admissions, a “minority” refers to people of color such as Blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans.

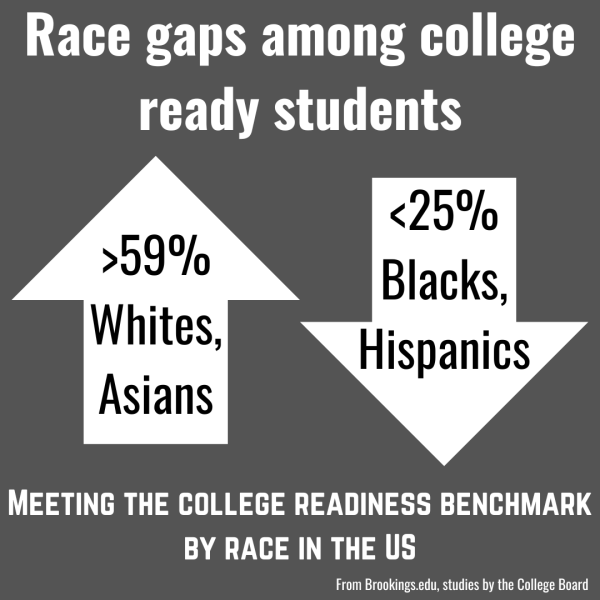

According to the New York Times, whites are institutionally more secure than minority races. Minority students are comparatively disadvantaged because of long existing systemic racism, especially in college admissions like SAT/ACT scores, educational backgrounds, extracurriculars, and more.

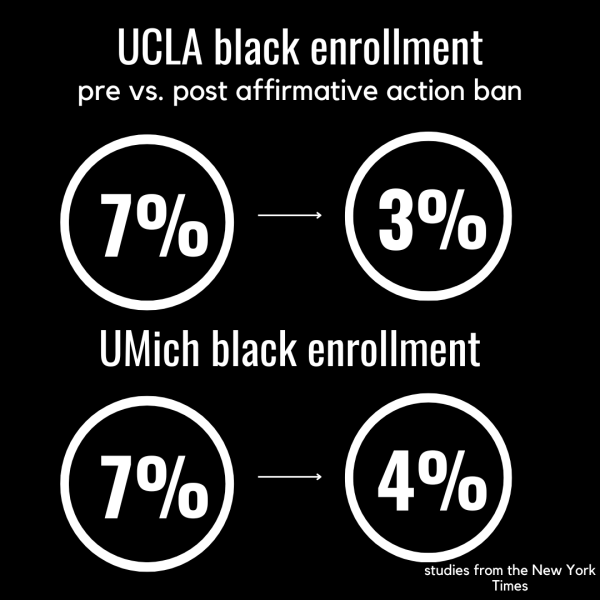

Racial imbalances persist in areas like the labor-force, income rates, and college enrollments. Affirmative action’s goal was to balance college admissions chances for students of color.

“Race or ethnicity is important when applying,” said Ava Edwards(‘24), president of the Black Student Union. “That way, colleges have a little more background on how much you overcome, and they can see how you may have things going against you depending on the society you live in.”

The attempt to recognize minority races can be traced back to 1954, with the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. In that case, the Court ruled that segregation in education violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution and required that all public facilities desegregated schools.

Following that ruling, schools gradually integrated their minority races into their student body. But, affirmative action didn’t begin with Brown v. Board. Interestingly, the origins of the phrase and concept itself had nothing to do with American education.

It was originally associated with employment. President John F. Kennedy created a Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity in 1961, and his Executive Order 10925 used the term “affirmative action.” Kennedy’s policy was to allow equal opportunity in a time where discrimination against African Americans in workplaces was normalized. The meaning of the term has changed to spread diversity in college and university pools.

In college admissions, affirmative action has become legalized through landmark cases establishing precedent. In 1978, the University of California v. Bakke case ruled in favor of using affirmative action policies to account for a history of excluding minorities, with the exception of illegalizing racial quotas.

Forty-five years ago, America had nowhere near the amount of diversity it has today. According to Brookings.edu, 79.4% of the nation was white in 1978, compared to 57.8% in 2023. So, 45 years ago, there was a greater incentive to help minorities achieve the same level of education as whites.

This idea continued into the 21st century, with the Grutter v. Bollinger case in 2003. The case reaffirmed Bakke in holding that the University of Michigan Law School could use racial preferences in student admissions and that this did not violate the Equal Protection Clause.

But, this year’s Supreme Court ruling reverses this precedent. According to Oyez, the SFFA sued the University of California and Harvard University on the grounds that race-based admissions programs violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Court sided with SFFA, holding that the Equal Protections Clause was violated and that there was no compelling interest for affirmative action in both Harvard and UNC. In doing so, a policy of race blindness – not weighting race as a factor in admissions – was imposed on college admissions.

Following the Supreme Court’s rulings, heated discussions ensued between proponents and opponents of affirmative action policies in college admissions.

Those in favor of the decision argue that affirmative action unfairly benefited minorities while excluded groups like whites and Asians were disadvantaged. They view the ruling as a step to move toward a fair, merit-based admissions system without race as a factor.

But to others, the ruling against affirmative action failed to understand that the existing inequity counteracts any chance at a merit-based admission process. The ruling also circulates worries about a lack of culture within college environments, which would lead to a loss of rich educational diversity.

“Moving forward, there’s the worry of schools being more of echo chambers in terms of ideas rather than diverse places of intellectual gatherings,” said Anantaa Banerjee (‘24).

Heading into fall and college application season, it appears that colleges and universities will try to tread around the Court’s decision.

“Institutions of higher education are working on different ways of incorporating inclusivity in their admission process,” said guidance counselor Ms. Facchini.

Many colleges have already begun releasing new supplemental prompts after the Common Application’s opening on Aug. 1. These questions purposely and indirectly ask about a college applicant’s background. Columbia University includes a new supplement asking an applicant to share views on their “lived experiences,” and Dartmouth College asks a question called “Let your life speak.”

The future of diversity at colleges and universities continues to be hotly debated.

“If I were to have a silver lining of the ruling, it would be that students are beginning to mobilize,” said Christina Huang, president of UNC’s Affirmative Action Coalition. “Students want to be heard, and they want to get involved, because this is our education, and we want to control the narrative.”